Projects

Identity Computation

An exploration of how machine learning systems process and understand identity, examining the intersection of algorithmic classification and human identity expression.

Fugitive Traces: Algorithmic Tracking and the Poetics of Bird Movements

Flying within the state of ambiguity -never fully on the earth nor the sky- birds project images of freedom for those devoid of wings and of scape for those under the gaze of their masters. In their movements, birds exhibit an embodied leeway, a fluidity that defies fixed categorization and resist continuous pattern recognition.

Amerindian Becoming. The Limits of Machine Learning Computation

According to some Amerindian myths, if you change the status of your body, a new identity becomes accessible. For Amerindian shamans, feathers, teeth, paints, and animal skins serve as elements of body modification and transformation. Through this altered ontological status, shamans engage in a cosmopolitics of war and diplomacy. Their bodily variations signify a radical transformation of their human status. Machine learning, as a project, aims to swallow up the entire world by quantifying and classifying it. In this universalist project, all the ontologies have the potential to be computed and incorporated int the recursive feedback loop of value extraction. Is the Amerindian becoming computable for this operationalization? Can machine learning compute the ontological variations according to Amerindian perspectivism? Amerindian Becoming is an installation that highlights the limitations of algorithmic classification and the dismissal of other taxonomies and realities in its universal project of control. In the eyes of algorithmic vision, how can you become a Being? How can you actively transform and question your algorithmic human status?

Amerindian Defiance of Machine Learning Classification

The European conquest of America was not only a source of wealth and power but also a gigantic laboratory in which the West proved its racial superiority and cultural exceptionalism. A vast epistemological project began to name and classify all entities of the New World, pinpointing as the ideal the western image of the Human Being. As white, male, autonomous and powerful enough to construct his own self, the modern, Western model of the Human was the measure against which all entities were to be compared. The famous Theodore de Brys engravings, informed by this model, represented indigenous people during the 16th and 17th centuries as irrational savages lacking souls, living at the verge of the human-animal boundary. How and to what extent, I ask, does this colonial project, along with its hierarchical epistemology and discriminating ontology, survive in current machine learning models? Amerindian philosophy, whose understanding of the world that the colonial project wanted to erase, defy the colonial bias inside machine learning functions, evidencing the narrowness of the conceptualization of actants and matter that it has to presuppose to calculate all the world. Thus, while Europeans had to test their superiority by probing the metaphysical lack of souls in indigenous beings, the latter looked for any material sign that probes in the Europeans bodies their godness, showing a divergent way to classify the world. Asking what a human is, I connect machine learning classification models to an anti-colonial classification of the world, where humans and non-humans become entities living in different ontologies and where an endless process of becoming establishes material foundations. Renouncing completeness, complexifying the physical border of the body and the world, accepting the permanent flux of matter, its abstractions and identities, speculatively emerges from the Amazon river a world of many worlds that defies the colonial functioning of Artificial Intelligence in its machine learning approximation.

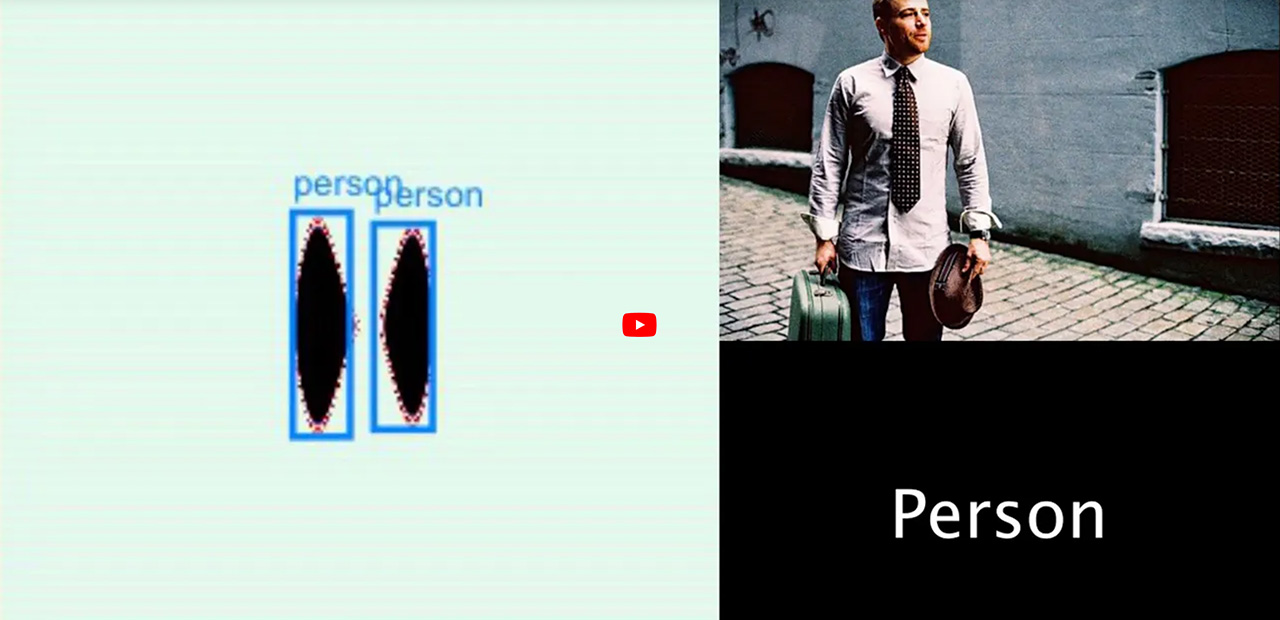

Entheo-Rithmic Inspection

In this visual research project entitled Entheo-Rhythmic Inspection, from 2020, a video constructed from a set of images designed by Nguyen et al., I have allowed myself to reflect on the limits of surveillance and control by preventing the identification and classification of the objects that supposedly appear therein in light of the perception of the algorithmic model. The more than 5000 images composing the Nguyen et. al. dataset were analyzed by the identification and classification model called COCO-SSD (Common Objects in Context), which is a large-scale object detection, segmentation and captioning dataset, by means of the RunwayML application, running on a local server. The images that were effectively labeled by the model were isolated and grouped with the objective of visually contrasting them with photos of those same objects, recognizable by human vision, housed in the COCO-SSD training dataset. Each of the resulting video clips from the recognized image categories were then merged together to create the final video. Finally, some of the images grouped into categories were used in the Playform platform to train a GAN algorithm to create new images. The images created with GAN were again sent to the COCO-SSD model to check whether, even with the modifications introduced by the algorithm, the object recognition model still recognized the same object category in the image, whether it changed its category or whether it did not recognize anything at all. The exercise made it possible to demonstrate that transferability of the AE, as well as the thesis of Tom White according to which different ANNs can share the same form of data processing and therefore the same classification system. Still from the video with the new images generated by Playform. With this exercise the viewer can evidence the abyss that in this case separates the visual perception of ANNs from human visual perception, contrasting the reality created by each of these perceptual models, delving into the limits and errors of algorithmic vision, and imagining alternative narratives to the tasks of identification and classification that these systems fulfill with the aim of monitoring and controlling.

The analytical language of artificial intelligence

Based on the categories of the COCO-SSD object recognition model, the user interface presents three other sections of images in the form of a grid that invite reflection on the arbitrariness that emerges in the classification of objects, but also on the prejudices that these systems reproduce. Thus, it is possible to see the reality and the worlds that are ignored by the algorithmic model, the diverse ways in which people make sense of the classification categories, as well as the interests and points of view that encourage and sponsor the development of these models, most of the time implemented in surveillance and social control systems.